The concept of the Anthropocene is largely associated with phenomena like the Great Pacific garbage patch, the sixth mass extinction and other events that not only will, but have already started to make the planet less inhabitable.

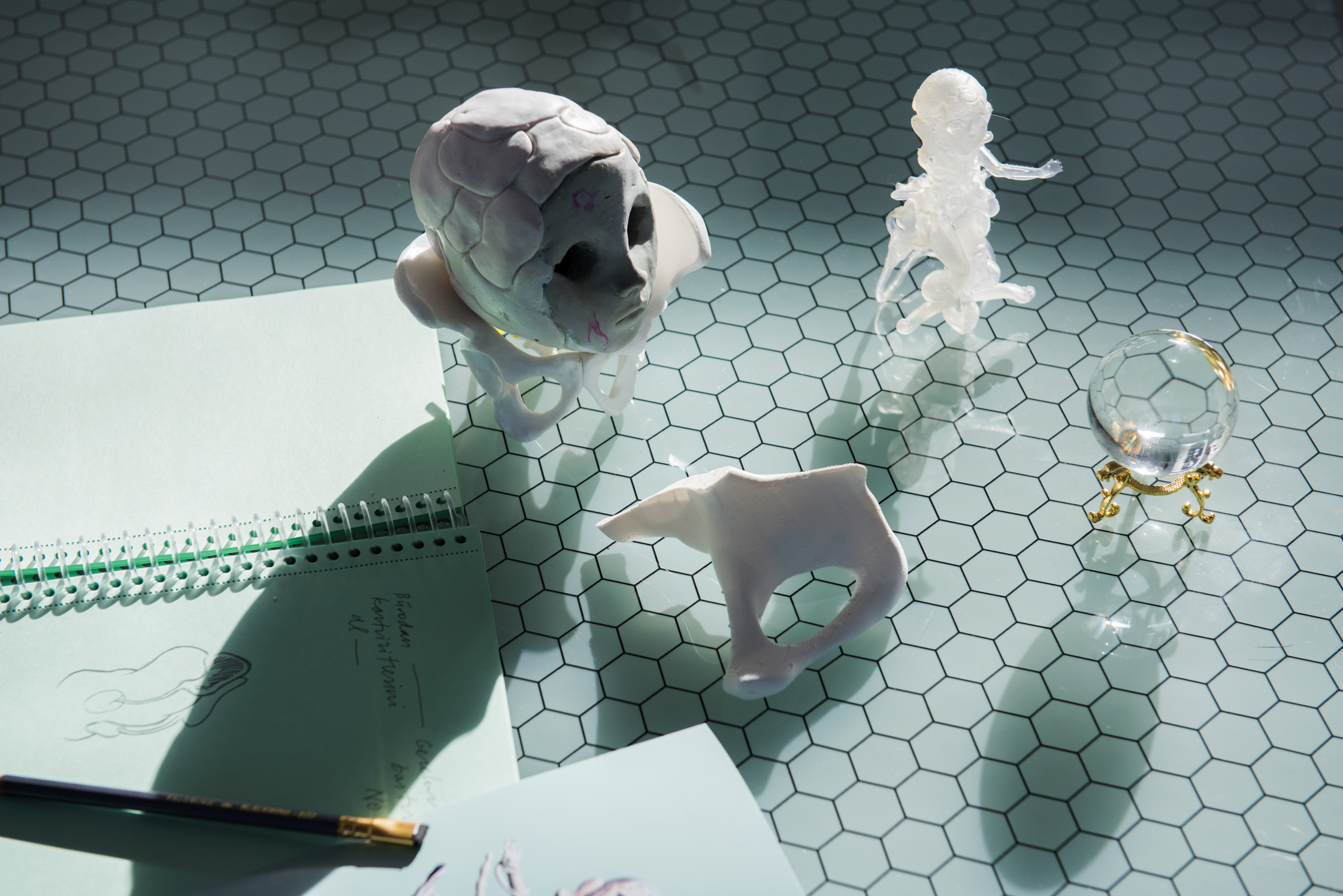

Pinar Yoldas refuses to tune into this song of doomsday, one that underlies most assumptions about our future on Earth. Instead, she extends her research and practice beyond humanity’s timeline. With her work ‘Ecosystem of Excess’ she has been speculating on lifeforms that will thrive even in a posthuman environment. The question of life becomes a question of design: “If life started today in our plastic debris-filled oceans, what kind of life forms would emerge from this contemporary primordial ooze?” If there’s one thing Pinar Yoldas is sure about, it’s that life—in whatever shape—will outlive humans.

This year at IAM Weekend, Barcelona’s internet age media conference, Pinar will address some of the biggest paradoxes in understanding ourselves as humans: our inability to think beyond our own existence and the imperceptibility of the consequences of our actions. “We’ve been here for only such a short time, why is it so hard for us to imagine that we will be gone?” For someone who treats biology with the toolset of an architect, our perceptual bubbles are nothing but a “design flaw in human beings” that can be adjusted at the intersection of science and digital technology.

As a Turkish-born artist who has lived in the United States for over ten years, Pinar Yoldas brings together multiple disciplines in her art work. She studied architecture, visual arts, and neuroscience and completed a PhD at Duke University in 2016. She refers to her work as “infradisciplinary” as it ranges from scientific research to video art, sculpture and installation.

“If you’re walking around and you have two penises and one vagina—then what are you?”

-

What you do as an artist can probably only be described using multiple hyphens. Picking up on your Twitter bio I’m curious about what an “overdesigner” does and how you understand the term eco-futurism—please tell us!

I studied architecture towards the end of the ’90s, and the beginning of the millenium. Architecture generally happens to be a field where everybody has very strong opinions. Every time I presented work to my professors it was labeled as being “overdesigned.” It wasn’t a praise, but more of a criticism—because I was overthinking and I was over-designing and that was a bad thing, because at that time design had to fit this idea of modernist minimalism. I experienced this for two or three years in a row, but it wasn’t until much later that I decided to adopt this label. For me, an “overdesigner” is someone who includes a lot of parameters in the design, which is a more wholistic way of thinking.

When I say “eco-futurism”, I’m thinking of an ecological movement that has the passion that futurism once had. We are, in fact, talking about the future a lot. Especially lately we’ve been seeing a large number of events, conferences, and exhibitions directed at new developments that we believe will affect society in some way or another, such as the rise of artificial intelligence. But actually, when you think about it in the context of the arts, futurism is a historic movement that started in the early 20th century. If you read the futurist manifesto, what they wanted was—and this is a movement that was born in Europe, on the old continent—for all the old institutions to be razed to the ground. They wanted a complete change while embracing the machine, the technology and the speed that comes with it. That movement of course had its flaws but it also had this passion. It’s actually an interesting movement to look back to, because it seems today we are living the futurist dream of the early 20th century, but we actually do not have this passion for transformation. Because the image of environmentalism is a little off—hugging trees and wearing pale colors—I was wondering if we can think of an environmentalism that is like the futurism of that time, which has this ultimate dynamism to it, this momentum, this power. So that’s where eco-futurism comes from.

“We’re just a blip in the history of the universe known to us.”

-

Perhaps this idea of “overdesigning” also follows a female strategy, one of excess and abundance—as opposed to the male principle of minimalism. When and why did you move from architecture to speculative biology? And did you ever feel that your concern is, at the core, also a feminist one?

Yes, it was! Chronologically speaking, I wasn’t designing organs or lifeforms until around 2007 or 2008. But the first ones that I designed were actually genitalia. I started imagining new sexual organs that could be attached to either: a male, meaning xy, or a female, meaning xx, body. I was addressing questions of biological essentialism—and this again comes from Elizabeth Grosz, a feminist thinker and a lot of other feminist thinkers who criticize this concept. Biological essentialism is the tendency to explain everything through biology, so for example, having a female reproductive organ would consequently lead to the idea of a female brain, of a female behavior and the idea of a female thought.

Having grown up in a restricted society I always thought that something was wrong with this kind of thinking. So when I was introduced to the work of thinkers like Elizabeth Grosz and the concept of biological essentialism, I thought that I should start designing organs that could belong to any body. For instance, if you’re walking around and you have two penises and one vagina—then what are you? Or if your entire body was made up of sexual organs, who are you, what is your definition? I just wanted to blur these definitions between male and female by creating these organs that did not belong to either sex. Perhaps one could also say that I used the principles of deconstruction and applied them to biology.

-

The discourse around the design of lifeforms and biomedia shows how we increasingly think of life as data, as something programmable, computable. Does your understanding of life follow the idea that biology can be completely expressed through code, when we refer to DNA, for example? Or, is there more to life than just information?

This is beautiful question! I don’t think life can be reduced to code only. There are so many things we do not understand about how life works and it is—in my humble opinion—too problematic to even believe that we can control all life and that we could become the master. I do believe that we have to practice everything with a certain sense of modesty and this is something that I think we may be forgetting more and more lately: to be humble.

I’m not against biotechnology, not at all. I actually love it and I use it in my work. I do believe we should support, cherish, and celebrate our curiosity. We have to explore, it’s our duty to look around and ask questions, to try to understand life. But to believe that we can master it and that we could become the sole decision maker in how life works? I think this is a little bit… [laughs] I think it’s just really, really morally wrong. I guess this comes from a long tradition, it’s not something that has just emerged, the fact that we put ourselves on this pedestal amidst all the other organisms and species and believe that we are—and this goes back to Christianity—the species that is made in the image of God. It’s just wrong. And we are finding out about how wrong it is right now as we destroy our ecosystem and as we destroy our kin on the planet.

“I’m not baffled by anything, I just want to hear more crazy stuff from science.”

-

You already brought up the role of the human in all of this and how we regard ourselves as the masters of life. Last year you also participated in an exhibition entitled ‘The World Without Us’, so I’m curious to hear more about your understanding of the posthuman.

I actually took the posthuman in the very literal sense when I started working on ‘Ecosystem of Excess’. I have a tendency to use these terms and to just take them very literally. So I really thought about a place where humans didn’t exist.

The first time I was introduced to the term was through Katherine Hayles, and again, there’s Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway and there is their posthumanism which doesn’t necessarily mean “after humans.” And then there is this more literal approach where we try to think of a timeline beyond the human. I really like both of them to be honest. I think both are very valuable intellectual tools for us to explore a highly complicated subject, which is the subject of the human in the 21st century.

Though the latter one, as in “a world without us” is even more of interest to me. It’s so hard for us to imagine the end of humanity, especially after populating the world with so many of us. But there is an explanation for it: because it’s even harder for us to imagine our own death. Death is a subject, just like old age, that we are not really interested in talking about and just like that we also don’t want to talk about the extinction of the human species. I’m interested in thinking about this, because it also connects to one other thing, which is the history of humanity set against the timeline of the universe. As we learn from Carl Sagan’s cosmic calendar if the universe is 12 months, humanity represents just the last hours of its last day. So we’re just a blip in the history of the universe known to us. We’ve been here for such a short time, why is it so hard for us to imagine that we will be gone? Why is it so hard to accept this? I think the moment we will be able to see a world without us, we will maybe have this paradigm shift in the way we approach our own lives and the lives of others on earth.

-

Can you tell us a bit more about the topic of your upcoming talk at the IAM Weekend 18 in Barcelona?

One thing I will touch on is isolation of human health from the planetary health, which is connected to the idea that we can master everything, our own health included. But there are so many examples of how we become miserable when we lose our habitat. This is one thing that I’ve been thinking about lately. The other thing has to do with imperceptibility. While the Anthropocene is being widely debated at the moment, I’m seeing it first and foremost as an aesthetic problem. It has a lot to do with our senses and our perception. Coming also from a neuroscience background, how we perceive, how we feel and how thoughts are being produced was always of interest to me.

As human beings our perception is limited to what happens in our immediate environment. In biosemiotics “umwelt” is the perceptual bubble that an organism lives in, so my umwelt is the bubble in which I can perceive things and outside my umwelt I can’t perceive things. For example if you think about your daily life: although we try to make good decisions, we’re still creating a ton of trash and contribute to this toxic cycle, because the consequences of our actions happen outside of our umwelt. There are certain things that are presented as a people problem in the environmental discourse, such as buying plastic bottles, consuming disposable items, excessive consumerism. But it’s hard to take action because it’s not happening where it’s supposed to happen, which is in our immediate environment. And this is a design flaw in human beings, we do not perceive or feel or understand beyond a certain distance. I’m not blaming humans, all I’m thinking is that the imperceptibly of the consequences of our actions is one of the main reasons that has brought us to this moment today.

-

With your work ‘Kitty AI’ you are speculating about the year 2039 and the first non-human governance. Personally, which species would you like to see ruling the world?

I really want Kitty AI to have a chance, actually. First, when making this project, I wasn’t so militant about it, and I thought it’s just this film that I made. But now that it’s been traveling and after seeing people’s responses to the character, I’m taking it more seriously. When I released the film, Trump hadn’t been elected yet. And after Trump, I started thinking that a Kitty AI could make a lot of sense. I even made a list why Kitty AI is much better than Trump: Kitty AI is attentive to citizens and you can reach Kitty AI very easily—it’s a two-way communication—whereas with Trump it’s that he tweets but he won’t receive your tweets, there’s just a one-way communication. Kitty AI speaks machine language plus all the languages spoken by its citizens, Donald Trump barely speaks English. Kitty AI looks like a kitten and Donald Trump—does he even look human? And of course: Kitty AI represents a cute pussy cat whereas Donald Trump grabs you by the pussy. So yes, lately I’ve been thinking that outsourcing this task to an entity that is not biased and that is not human might not be a bad idea at all.

-

What is the most recent scientific finding that baffled or fascinated you—and why?

[Laughs] Nothing baffles me anymore. But, yes of course, a couple of new things caught my attention recently, that I’m excited to maybe even use in my work at some point. One of them are neuromorphic chips and a couple of developments in neuroscience showing that neurons work a little different than we have been thinking for over half a century. Another thing is organ printing, which has always been interesting to me. It’s not a new thing, but I just found out that organ printing is now able to work with other types of cells. Earlier, I believe, it was pretty much limited to skin cells. Those developments are exciting to me! So to sum up: I’m not baffled by anything, I just want to hear more crazy stuff from science. And I don’t think we hear enough yet. I want to be shocked every single day.

-

This year you also started teaching at UC San Diego in the arts department. Would you like to share some insights with us on the experience of teaching and how it relates to your work?

It is very connected, this quarter especially. One of my seminars is called Ecology meets Media Art: The Good Anthropocene. In this class we’re looking at artworks and design projects that address the notion of the Anthropocene, but most of them are actually very dark. I’m encouraging my students to come up with four to five things in our lives that they believe should be improved. We’re basically thinking about speculative design projects that can pave the path to a different Anthropocene. Because it is possible! We just spoke about the end of humanity, all these ideas might seem kind of dark, but maybe they aren’t. I’m optimistic, actually.

We’ve met with Pinar in the run-up to her talk at IAM Weekend 18 in Barcelona. The annual internet age conference takes place April 27–29 this year. If you’re in town, make sure to check out the other IAM speakers and the full program. If you can’t make it to Barcelona, you may want to read our interviews with the founders Andres Colmenares and Lucy Rojas on FvF and Ingrid LaFleur, who will also hold a talk this year.

To keep up with the scientific findings of Pinar, we recommend following her on Twitter. Pinar’s work and her exhibition schedule can also be found on her website.

Interview: Vanessa Oberin for FvF Productions

Photography: Kenny Hurtado for FvF Productions