Four figures gaze out over a map of the Alps. The photo is Luigi Ghirri’s, ‘Salzburg, 1977’. At first glance it seems ordinary, maybe even familiar, though Ghirri isn’t particularly well known. But equally, the image is surreal.

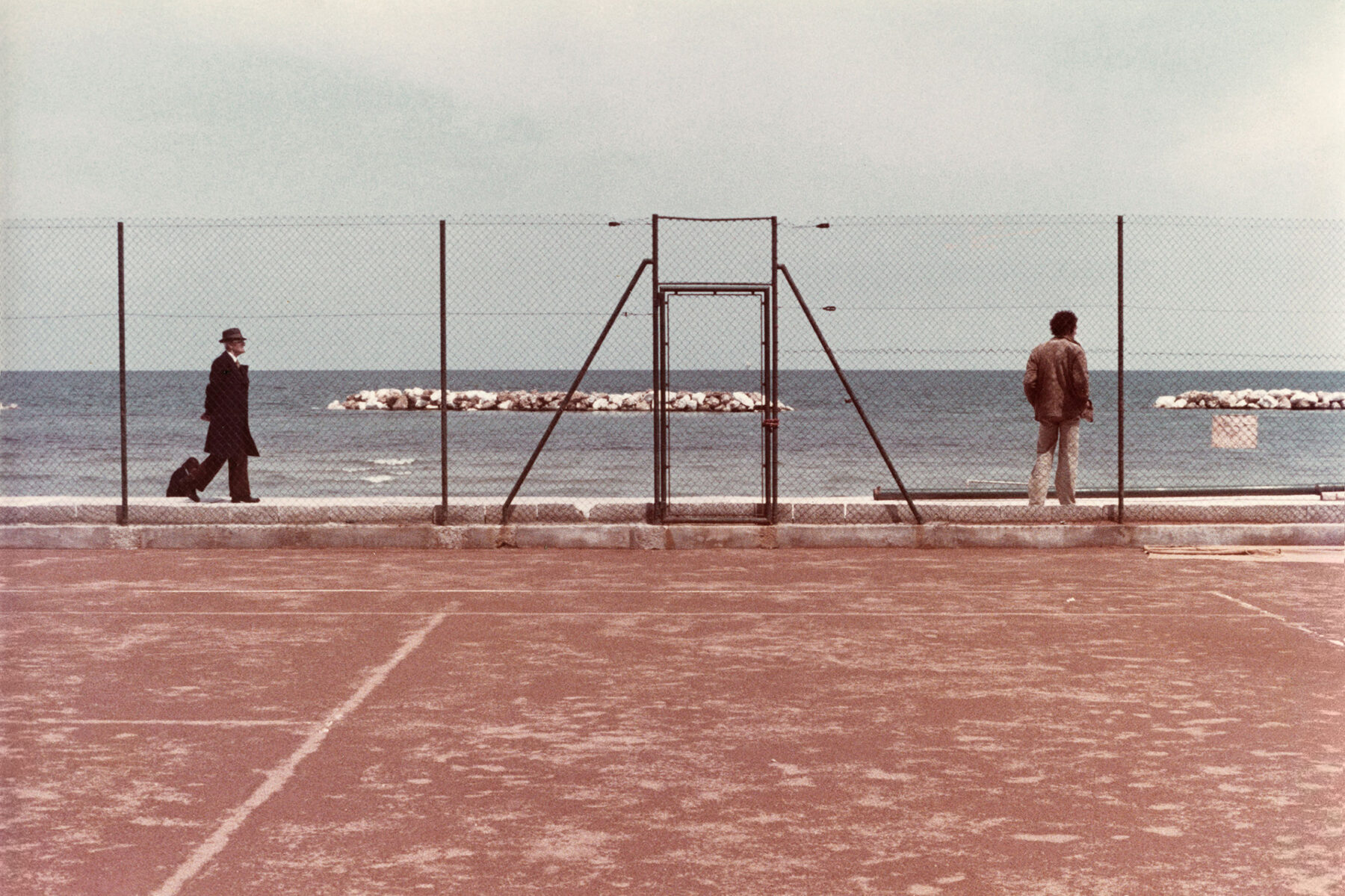

The four figures appear as though they are looking into the distance, but there is in fact no distance. They’re probably planning a route to walk on their holiday in the Alps. There’s a tension between what you can see and what they can see. This tension is Ghirri’s domain. Throughout his career as a photographer he worked to reconsider and reframe the mundane, making the familiar seem strange. In 1982, after dedicating 10 years to photography, Ghirri described this as his duty to “see everything that has already been seen, and to observe it as if I were looking at it for the first time.”

Ghirri’s intention produced an indispensable body of images. His early work has been noted for its proximity to Andreas Gursky’s abstract mode of photography. In The New York Times his cerebral style was likened to the writings of Italian postmodernist author, Italo Calvino. Rene Magritte’s surrealist paintings were hung beside Ghirri’s photos for comparison in the Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, in an exhibition curated by Thomas Demand—a contemporary conceptual artist, who cites Ghirri as an inspiration to his work. And when Call Me by Your Name director Luca Guadagnino was asked to name his greatest influence at a screening in New York, he announced it to be Ghirri. The response was one of bemusement. Ghirri’s photographs are modest in subject and in scale, most no bigger than postcards. What’s given rise to this acclaim?

Ghirri tended to think of his work in sequences. ‘Salzburg, 1977’ was part of ‘Diaframma 11, 1/125, luce naturale’, in which he photographed people, but always from behind, or looking at something, or in the process of being photographed by someone else. “I wanted to give the person an infinite number of identities,” he wrote in the introduction to ‘Diaframma’. “From photographer to subject, from being looked at to being an onlooker.” The people he chose to photograph are irrelevant. They are mostly anonymous, their faces obscured. Rather than trying to photograph people, he was using them to express that there is another point of view available, besides the one you see. It’s both the same as your point of view, as you’re looking at the same thing, and different, because they are in the picture. Looking at the people looking at a map makes you feel as though you are looking at the map as well—but you’re not. The photo is describing another perspective.

“I wanted to give the person an infinite number of identities, from photographer to subject, from being looked at to being an onlooker.”

This comes as somewhat of a surprise if you consider his previous career. Ghirri trained and worked as a landscape surveyor for 10 years before committing to photography in 1970. His job involved mapping out points of land and the distances and angles between them through meticulous measurements and calculations. By marking out these lines he would determine borders of property and ownership. There was no room for interpretation.

On another level it comes as no surprise at all. Ghirri’s friend Vittorio Savi once described his time as a surveyor as, “in part a betrayal of his vocation for photography, in part a preparation.” And Ghirri himself described that an aim of his was, “not to make photographs but charts and maps that might at the same time constitute photographs.” His previous career pervades his work. Each individual picture is composed with cartographic precision. In ‘Paris, 1972’, another photo from the ‘Diaframma’ series, Ghirri captures a boy from behind, looking at an Eiffel Tower trinket he’s holding up. Its curvature is in perfect calibration with the round of his cheek. It’s uncanny.

Now take a step back. In relation to the other photographs in ‘Diaframma’, the image can be seen as a point on a clearly defined chart. “Each piece requires the patient work of fitting it in,” Ghirri wrote. “Interlocking it with other pieces, measuring it and contrasting it.” Looking from ‘Salzburg’ to ‘Paris’ you might recognize Ghirri’s careful measurements and comparisons in theme and composition. Through this patient work he has charted a particular kind of mental space. James Lingwood, director of Artangel and champion of Ghirri’s work, explains in interview with FvF that the ‘Diaframma’ sequence “isn’t about the personality of any one figure, but it’s about a way of looking.”

Another step back. ‘Diaframma’ was just one series within Ghirri’s first major exhibition in 1979, Vera Fotografia, or ‘True Photography’. Each set of images was created and curated in painstaking relation to the other 13 photographic sequences that ran alongside it. He focused on specific motifs—“objects charged with desires, dreams,” he writes: “windows, mirrors, stars, palm trees, atlases, globes, books, museums, and people seen through images.” In its whole, Lingwood describes it as a “reflective, ruminating work about the nature of images, and the role of them in the formation of modern identity.”

“I get the impression that behind what I see there is another landscape, one which is the true landscape, but I can’t say what it is, nor can I imagine it.”

One last step back. You are in Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, where Lingwood has curated the first major retrospective of Ghirri’s work outside of Italy since his death in 1992. Later in the year, the exhibition will move to Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, then on to Jeu de Paume in Paris in 2019. In the museum bookshop, editions of the collection are available in German, Spanish, French, and English. It is titled, The Map and the Territory, and comprises the first decade of Ghirri’s work as a photographer. Looking around, you might draw lines between these images endlessly. A sense of familiarity sets in.

But still, something feels strange about these plain little photos. “I get the impression that behind what I see there is another landscape, one which is the true landscape, but I can’t say what it is, nor can I imagine it,” Ghirri wrote in an article in 1986. And the statement chimes with you, as though his point of view has quietly made its way into your mind. Because it’s hard to say, as you plan your route through the exhibition, whether you’re looking over his photos, or over a map—or over an immeasurable territory.

The Map and the Territory exhibition runs until 20th of May 2019, in Museum Folkwang in Essen, Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, and finishing at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. The book is available for purchase from the MACK website.

Thank you to Museum Folkwang and MACK for providing the images, and to James Lingwood and Ed Spurr for providing the insight.

Text: Louis Harnett O’Meara

Photography: Luigi Ghirri