The California-born and Berlin-based artist on the musicality of American Sign Language, channeling her anger into mathematical diagrams, and standing by her principles.

“I’m starting to find that headlines are becoming a blur at this point,” says Berlin-based artist Christine Sun Kim. Sat in the lounge area of her Wedding apartment, with her sign language interpreter Beth Staehle skyping in from Paris, Kim skips easily between conversations about her visual art practice and contemporary politics. From discussing her worries about Trump’s America to Brexit Britain, immigration to Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil, it is clear that Kim is very preoccupied with what’s happening in the news. Where once she believed that governments were in place to protect us, now, as a new mother exposed to images of migrant children in cages, she’s not so sure. “I think considering the current state of the world’s affairs makes me realize even more that the government doesn’t necessarily have our best interests in mind, especially not those of marginalized groups,” she says sadly.

Kim doesn’t just talk openly about political issues, she also puts her ideals into practice. She recently made headlines as one of the eight artists who withdrew her artwork from the 2019 Whitney Biennial in protest against the museum’s failure to remove Warren B. Kanders—who has ties to the sale of military supplies, including tear gas—from their board of directors. Motherhood yet again was a driving force behind this action, as Kim’s statement in The New York Times read: “As a mother to a two-year-old daughter, it terrifies me that my work is currently part of a platform that is now strongly associated with Kanders’ teargas-producing company Safariland. I do not want her to grow up in a world where free and peaceful expression is countered with means that have left people injured and dead.”

“I want my ideas to be accessible. I want to pull people in and to open their minds.”

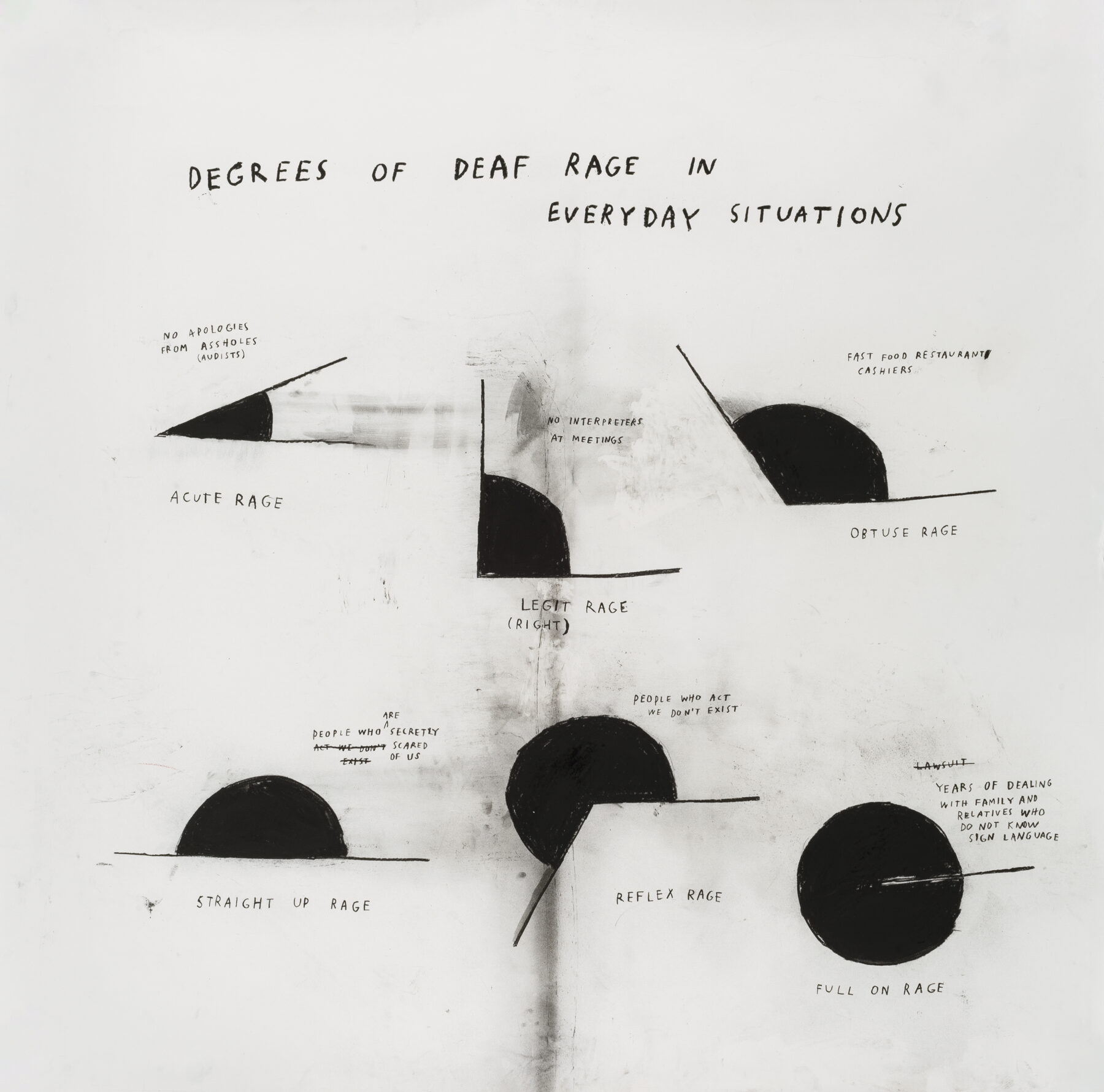

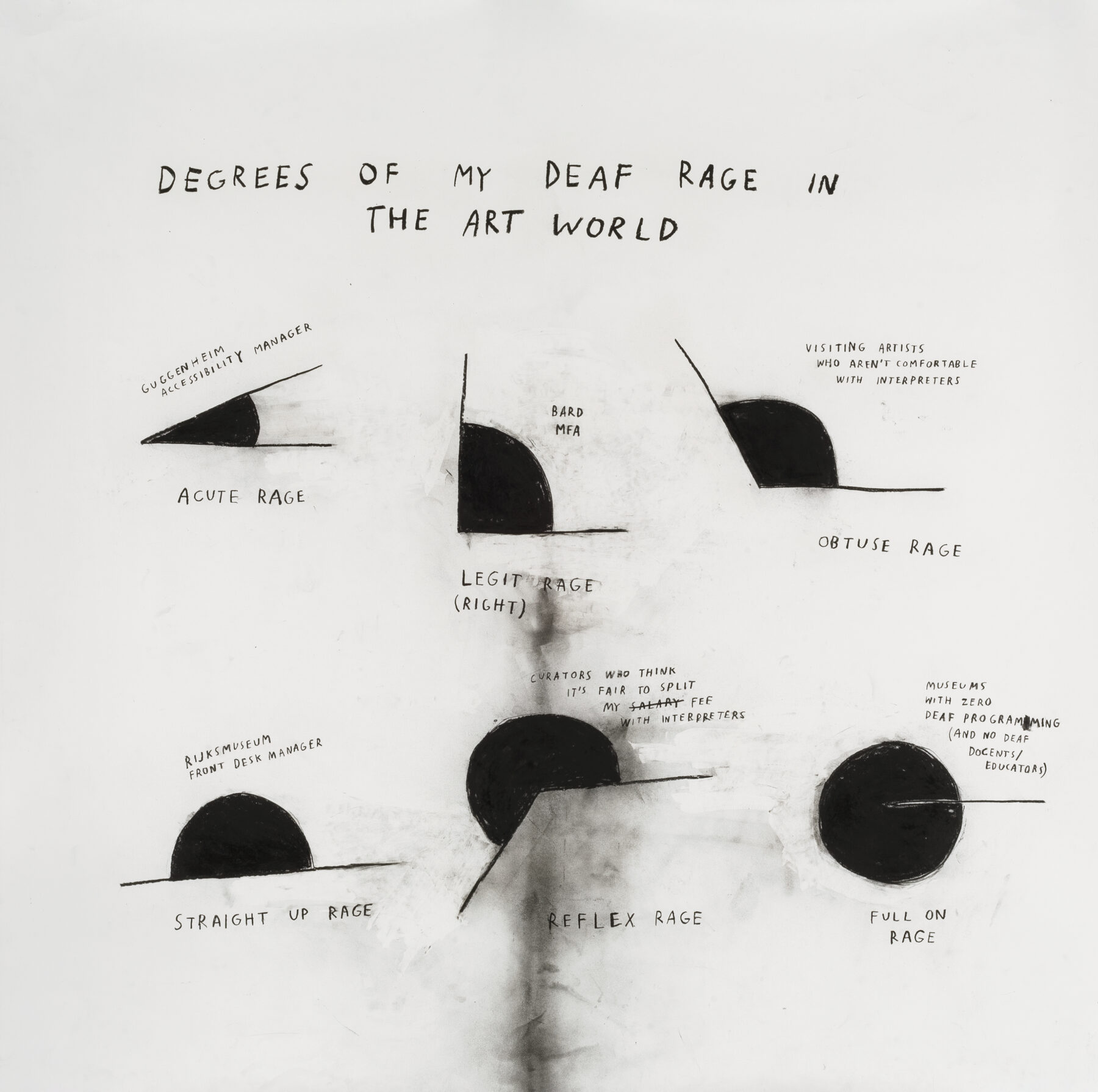

Kanders has since resigned from his role on the board, and Kim, along with her fellow protesters, has permitted her work to remain in the galleries. And it’s a good thing too, as the presence of the series Kim submitted for the biennial makes as much of a statement as it did in its absence. Entitled Degrees of Deaf Rage, the collection of six charcoal drawings depict angles of varying degrees, which are each labeled with infuriating experiences Kim has experienced as someone who has been Deaf (Kim prefers to capitalize the word “deaf” to denote a cultural group) since birth. “Deaf rage is a real thing,” explains Kim. “In the Deaf community it’s something we know so well because we’ve all gone through it.”

The series of six drawings speak to both rage-inducing incidents applicable to the entire Deaf community—such as interpreters who self congratulate for “helping us” and people who are secretly scared of Deaf people—as well as occurrences that are specific to Kim’s experience in the art world. So far the response has been resoundingly positive. “A lot of my Deaf friends are just like, ‘girl, I agree,’” says Kim with a smile. “Some have light disagreements and say, ‘I’d have given that the acute angle rather than the obtuse angle.’ I think it’s funny because people are arguing about what is the smallest and biggest offense for them, which is really interesting,” she continues.

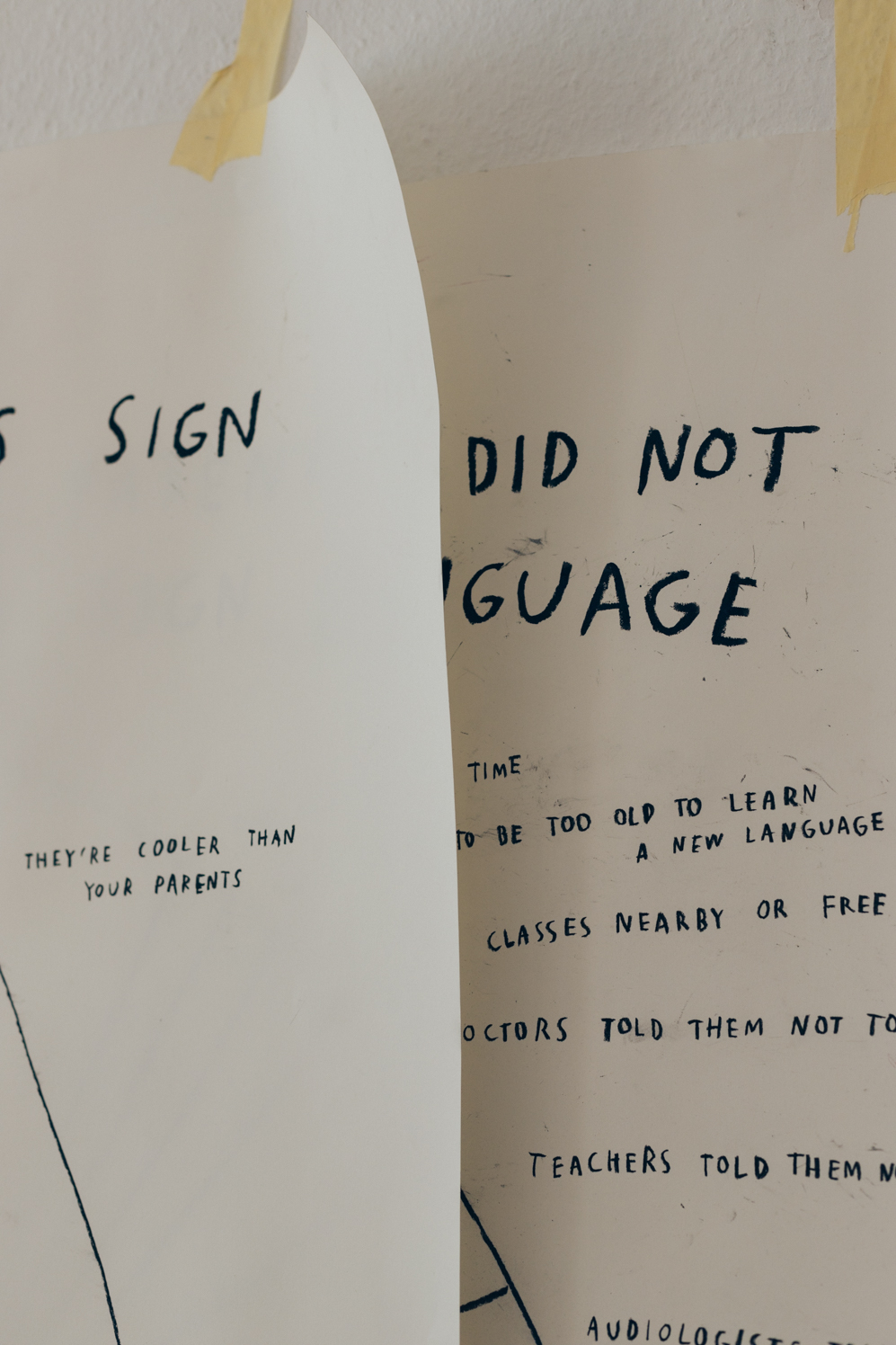

For her latest series of drawings, Kim has stuck with mathematical formats. Currently taped up across the walls of her bright and airy studio, they use pie charts to demonstrate the variety of reasons for choices Kim has made in her life. “I like to work with formats that are easily communicable to any audience,” she says about the work. Ranging from explaining “why I stopped going to speech therapy” to “why I don’t read lips,” these drawings are due to be shown to the public for the first time at the MIT List Visual Arts Center in February 2020.

At the same time as discussing serious socio-political topics, Kim’s drawings are also brimming with humor and personality. In one pie chart, for example, the main reason she gives for watching television with closed captions is that it is good when watching rap battles. “I use humor because I want my ideas to be accessible. I want to pull people in and to open their minds,” Kim explains. She also says she always tries to maintain a degree of humor in her personhood to make herself more approachable. “I communicate differently, and sometimes people can get surprised when they encounter me. Humor can make that situation a little bit easier.”

“I could maybe count on my hand how many Deaf artists there are, and that’s horrible. We are skilled in visualization, so I think it’s a shame that there aren’t more of us.”

Despite currently openly discussing her Deaf identity in her artwork, Kim was initially reticent to let this define her artistic practice. “From the minute I was born, I became a political entity, which is kind of dumb,” she says, explaining that there are many other facets to her identity—such as being the child of Korean parents that emigrated to the U.S.—that inform her practice. “If I had had the opportunity to show at the Whitney 10 years ago I would have never picked Deaf rage,” Kim continues. “But now I feel like people are ready to hear about it, and that I’m at a place in my career that I feel safe to share this information.”

Prior to her Deaf Rage drawings, Kim worked largely in the field of sound. She was first inspired to work with the medium upon her first-ever visit to Berlin in 2008, when she was unaware that the city would later become her permanent home. “I think my mental capacity kind of expanded here,” she says. While previously dismissing the medium as something that wasn’t a part of her life—“in a way I think it was secretly an act of protest to show that I could live without it”—she came to realize that she actually had a unique understanding of sound, developed through constantly observing how people behave and respond to it and being taught what she terms “sound etiquette”—not slamming doors or scraping utensils on plates—whilst growing up. After completing an MFA in Sound and Music at Bard College in 2013, sound became the backbone of Kim’s practice. By looking for ways to represent sound visually—whether through vibrating objects, conducting a choir to sing through facial expression or creating visual scores—she came to notice similarities between American Sign Language (ASL) and music. Kim shared these findings as part of her popular 2015 TED talk, which she called The Enchanting Music of Sign Language.

The idea that sound doesn’t have to be experienced through the ears is evident while talking with Kim. Observing her sign to her interpreter Staehle, who in turn translates Kim’s replies into spoken word, one can’t help but notice the rhythmic and melodic nature of ASL. The other thing one can’t help but notice is the immense amount of trust Kim must have for Staehle, who is one of her core group of interpreters. When asked about this, Kim pulls out her phone’s address book, showing me a section of names with ‘TERP’ after them, an abbreviation of interpreter that is also used in the military. “It does feel a bit like voice dating. It takes a while to find the right fit,” Kim explains. “It’s such a collaborative form. I have to work within their personality and parameters. If the interpreter’s shy, I come across shy. That can be hard for me because I’m quite social and like to meet people,” she continues. “It does require a lot of trust. I’m lucky because in interviews like this I can look back at the transcript and see the word choices the interpreters have used. Sometimes I see through that experience that an interpreter didn’t really capture my voice, and I can decide whether or not we should work together again.”

Kim has had access to interpreters since she was a child at school in California. “I’m the perfect result of legal protection and laws in the U.S. I didn’t have to pay anything out of my own pocket for this kind of equality,” she says, explaining that she’s witnessed first-hand other countries where there is less protective legislation for members of the Deaf community. “Even here in Germany, which is one of the richest countries in the world, people are still fighting to get more captions on television, which kind of blows my mind,” she continues. Another thing that amazes her is the lack of representation of Deaf artists in the cultural industries. “I could maybe count on my hand how many Deaf artists there are, and that’s horrible. We are skilled in visualization, so I think it’s a shame that there aren’t more of us.”

Christine Sun Kim’s Degrees of Deaf Rage

In order to combat this lack of representation, Kim plans to continue creating work about Deaf identity in order to promote greater awareness of her community. “I’d like to do more public art projects,” she says, referencing to a billboard she recently created in London for Art Night which declared: “If sign language was considered equal, we’d already be friends.” She also wants to experiment with choreography, and discover an authentic way to combine dance with ASL, as while sign language is accepted and visible in U.S. media, she finds that its usage can sometimes have a hint of fetishization. “A lot of music videos I’ve seen where sign language is incorporated have been created from a hearing perspective. I’d like to see how it would work from a Deaf point of view,” says Kim. “ASL is my native language, it’s my mother tongue. I know how to use it best.”

Christine Sun Kim is a multi-disciplinary currently based in Berlin whose practice traverses the mediums of drawing, video, performance, and sound. Her recent work explores her Deaf identity and promotes greater understanding of the situations members of the Deaf community encounter on a daily basis. She is currently showing six drawings as part of the Whitney Biennial in New York City and will be showcasing her latest series of pie charts at an upcoming show at the MIT Visual Arts Center.

Text: Emily May

Photography: Jenny Peñas

-2018-纸上炭笔和油画棒charcoal-and-oil-pastel-on-paper-125×125-cm-framed-size-126×126-cm-1-1800x1812.jpg)