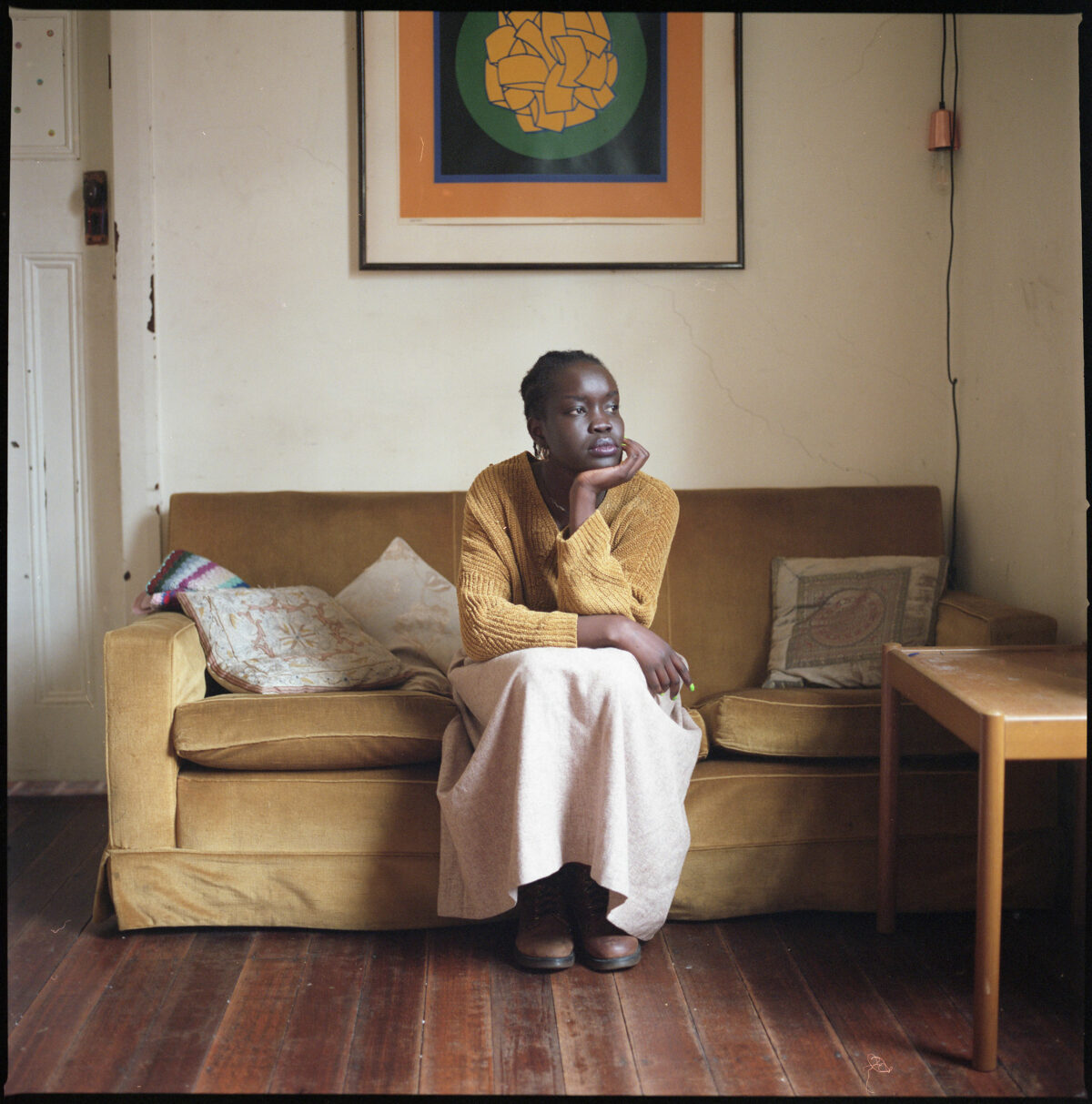

The idiosyncratic work of photographer Atong Atem is distinctly personal. Not only does it urge you to understand the individual behind the lens, but every aspect that frames her existence.

Though her website assured me she is “alive and doing okay,” getting a hold of the Melbourne-based photographer and writer Atong Atem seemed impossible at first. I learn about the 28-year-old’s busy schedule—with commitments including a recent show at Sydney Contemporary and heaps of new projects in the making—when we meet at Padre Coffee, one of Melbourne’s open-plan coffee shops in Brunswick, an area abundant with art spaces and studios that backdrop the city’s towering skyline. The sleek, capitalist setting seems far removed from the city’s indigenous history, and indeed, Australia’s in general. Originally known as Narm—an indigenous name that many are demanding to be reinstated—Melbourne is filled with a vibrant community of artists, creatives, and activists who are using their practices to explore related issues. Atem is one such artist. “I feel like a lot of people forget that Australia is a presently colonized place. That means something. You feel like Melbourne’s the world’s most liveable city and it’s super hip and cool, but it’s still in a colonial country, it’s a colonized space,” she remarks.

This profile is part of Visually Speaking, a content collaboration of Unseen and Friends of Friends. Learn more about the series at the end of this story.

Atem is grateful to be in this city, to be educated on first-nations activism by collectives such as Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance, by people who have lived and personal relationships to it. Being friends with some activists has informed the way she relates to and frames her own identity, which she considers to be multidimensional; she identifies as a South Sudanese writer and artist living in Melbourne. She intentionally rejects the identifier ‘Australian’ or, as she puts it, “to identify with an existence here that is not mine to take. I don’t think that means I shouldn’t make work here, it means that I have to understand who I am in this time and space in history, and what kind of work I am making without taking up space or taking away space from first-nations people.” In practice, this translates to her series Third Culture Kids, which focuses on the social and cultural identities constructed by first and second-generation Africans living in the diaspora. Decked in African wax prints paired with Western staples such as Converse sneakers, the 20-somethings softly gaze in Atem’s direction as they pose in front of floral backgrounds. Atem comes across as a similarly vibrant person; I salute her fabulous leopard pants and am instantly drawn in her by positive energy.

Atem’s story began in Ethiopia and continued in the Kakuma refugee camp in Nairobi, Kenya, where her family settled after escaping the second civil war in her parents’ home country, South Sudan. Her family arrived in Australia when she was six years old. Atem recalls feeling alien in Australia, being surrounded by predominantly white people. She watched her mother work extremely hard—due to visa issues, her father only reached the country years later—while caring for five children. She didn’t speak English, but she made it work. Atem refers to her father, a linguist and political journalist and writer, as a wealth of information, particularly on South Sudanese and broader global politics. Her parents’ narrative often occurs in our conversation, to the point that Atem says it “feels like I’m recounting someone else’s story because I feel so situated in Australia now having grown up here.” Would they ever move back? She doesn’t think so, considering the continuous unrest in the country. “But I fantasize about them retiring somewhere along the Nile, drinking cocktails with the sunset in the background,” she says, smiling.

“As migrants, there is a sense of responsibility and duty to perform and to be as outstanding as possible, which doesn’t leave a lot of room for personal or individual expression, let alone creativity or a creative career.”

While most of her work sits on a fairly political foundation, Atem’s visual language is deeply rooted in South Sudanese heritage, and its rich culture of dressing in particular, which her intricate studio works reference in the form of wax-print fabrics and headdresses in bold, clashing colors and patterns. She names storytelling, performance, and costume as the three pillars of her relationship to cultural pride. Her subjects—her friends, family members, and herself—pose with strength and grace in front of hyper-patterned, often floral, environments. The staged photographs subvert an ethnographic gaze of colonial times, speaking to the importance of creating and owning one’s own narrative. They’re celebratory, too. “It’s a moment, a celebration with your best outfit, and you perform.” Her self-portraits, which are not just her most intimate, but probably strongest works, are her way of bringing fantasy to life. She paints her face, glues diamonds on it, and accessorizes with fluorescent clothing. “With photography, you’re already making a world within that frame. I’m interested in the ways I can push this world-building by constructing characters that could exist in a future where everything is safe,” she notes.

Her vast interest in technology, and camera technology in particular, also influences her notion of the future. “The production of the camera informs the way we use the camera now, even very literally in terms of ways film cameras weren’t designed to photograph dark skin until some dude in a fucking furniture factory was like, I have this mahogany furniture that I want to take pictures of and Kodak was like, yeah buddy we got you,” she exclaims. Is her desire to self-referentially portray people of color part of a quest to interrogate the imbalances that continue to exist in photography, and in the arts in general? “I still have power over the people I’m taking photos of. Considering the history of photography and the ways black people have been portrayed historically, it’s really important for me to interrogate that power dynamic, and to make my work as collaborative as possible,” she says.

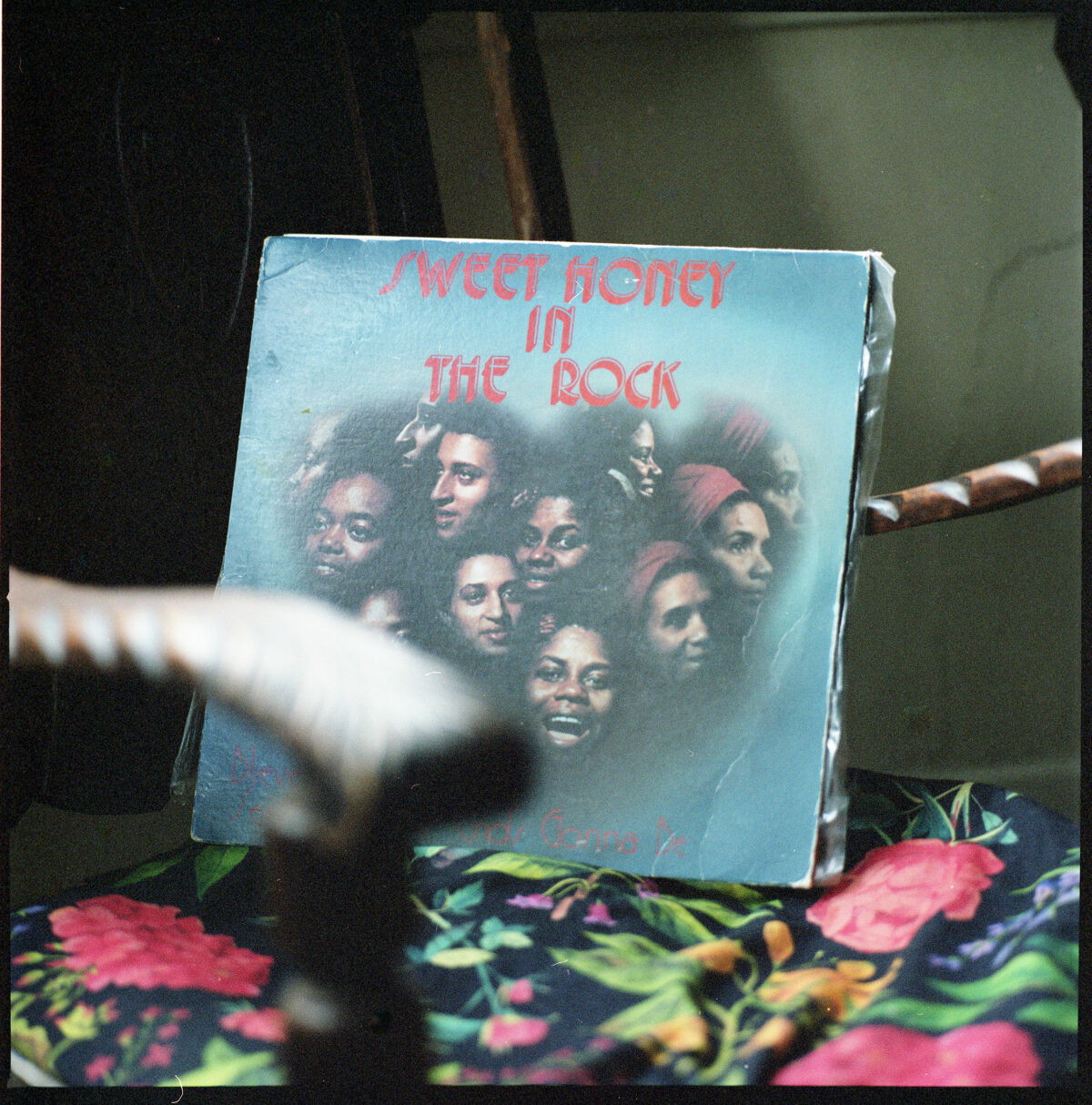

Atem describes her process as very organic, referring to an extensive mental catalog she constantly pulls from. “Growing up extremely poor, being a refugee, being isolated on the central coast where I grew up, and having constantly been in places where I’ve just had to use my own imagination, helped me develop a really broad and constantly growing personal library of references.” This makes the way she works uniquely circular; she constantly reframes and reconsiders her own perspectives. On and prior to production, a lot of it is experiential—playing with light, colors (she always uses different color temperatures), patterns, body shapes, props, and more—which takes off a lot of pressure. She says she approaches writing—alongside photography Atem has written for magazines such as Gal-dem—in a similar way, with it being very intimate, touching on big, but very personal experiences. “When I write it feels like I’m unearthing myself, my thoughts, my identity. It feels complimentary to my visual work; I don’t see a separation.”

One of her most recent series, Portals, doesn’t rely on colors or symbolism. The black and white images, which she exhibited in a large-scale format, are powerful through topography, through the way the facial and skin features of her sitters—again, all of them were friends—map the depictions. “I wanted them to be big so you can see everything,” she explains. The exhibition also meant some personal backlashes for the artist, driven by the way some white viewers digested the works. “It doesn’t matter that people don’t understand them, that’s not important in image-making,” she pauses. “But it did matter when it felt like people that I have a really personal relationship to had their bodies and images digested in a gross way. My intention was to almost peel the front layer off my really bright photos and reveal something else underneath, which, to me, is just as beautiful and just as pretty.”

Atem doesn’t feel the need to preface her narratives as much anymore: “It’s evident in my work and, unfortunately, it’s evident in my existence as a black person in the world. There’s a lot of things I can’t escape, and that I don’t want to escape as well. When it comes to colonialism, anti-blackness, and representation, the best thing I can do now is to just amplify other people’s voices. I’m not an expert on it but when I’m inspired to talk about my experience, I will talk about my experience openly.” Atem admits that, in the back of her mind, she feels a need to incorporate her family in her art in some major way—a need that originally underpinned her academic calling; Atem studied architecture before completing her fine art degree at Sydney College of the Arts. “I grew up with quite a strong emphasis on living life as practically and helpfully as possible whilst flourishing and taking advantage of the opportunities my parents sacrificed for me,“ she begins. “As migrants, there is a sense of responsibility and duty to perform and to be as outstanding as possible, which doesn’t leave a lot of room for personal or individual expression, let alone creativity or a creative career or whatever. For a long time, I believed that my only options were academic.” Ironically, her visit to South Sudan in 2011, the year the country gained independence from Sudan, changed that perception.

Placing an overseas vote in the national referendum empowered her to forge a personal connection to South Sudan that was outside her parents’ relationship and the colonial-refugee narrative. She was there to celebrate the nation’s first day of independence and not only encountered many more cultural spaces than anticipated, but was also met with her relatives’ enthusiasm for her artistic inclination and ambitions. She halts for a few moments when I ask about a potential desire to relocate. She thought about it while studying architecture, but, today, I assume the answer to be no. “Rather than me trying to force myself into an existing narrative I just need to figure out ways that I organically am already part of that story. For me, storytelling through visual art is something that I can do, and would be doing regardless.”

She cites a recent article that challenged African children of the diaspora with a sense of saviorship towards their birthplaces. It highlighted the existence of people on the ground, people who will enact the most profound change. “They’re not waiting for us migrant kids to come and bring in our Western knowledge,” Atem notes. How did her stay challenge her notion of belonging, considering that she was home for the first time in her life? Did it make Australia feel more like home? “It made me feel strange calling a place that I have no actual relationship to home. I realized I exist pretty firmly in a liminal space that is neither that home or this home or whatever.”

She is currently preparing for a solo exhibition at Melbourne’s Immigration Museum, the theme for which is truth. “I think it’s going to be the biggest thing I’ve done in my art career so far so I’m kind of shitting myself a little bit. But it’s going to be fine,” she says, laughing. Atem has yet to determine her vision for the project. What’s certain is that her work is never a definite statement. That instead she asks questions. She may still explore being a person of color and being South Sudanese, but more specifically, how relationships to family can define our relationships to entire cultures. “I don’t have to speak for anyone but myself. That’s the biggest thing I’ve come to learn.”

Atong Atem is a South Sudanese photographer and writer based in Melbourne. Her body of work explores the societal and cultural identities lived by first or second-generation Africans living in the diaspora. Her father, a journalist, writer, and linguist, has recently published a memoir recounting his personal history alongside South Sudan’s political history.

This profile is part of Visually Speaking, a content collaboration of Unseen and Friends of Friends. Exploring image production as a socio-political tool to uncover unseen realities, the series eschews links to fast and constant image production that the digital age undeniably promotes. Through intimate profiles, the series presents four established and emerging photographers who honor a slow process, unfolding their daily lives and creative practices. Whether they explore their own personal and cultural histories, investigate societal issues, or turn to loved ones, they uniquely differ in their ways of working and the realities they are influenced by.

Text: Ann Christin Schubert

Photography: Anu Kumar, Atong Atem, Courtesy of the artist and MARS Gallery